As the historical term Indochina implies, Mainland Southeast Asia was a crucible of cultural influences originating from both India and China. As early as the 1st century CE, an ancient kingdom known as Funan controlled the trade routes of southern Indochina. By the 6th century Funan had split into two successor states: the Cambodian Khmers in the south and the Mon-Dvaravati in the northern region that would eventually become Thailand.

These ancestors of the Thai came to rule a large area of north-western Indochina situated between the Burmese and Khmer empires. Over the centuries, numerous wars were waged by these three rival states, whose territorial boundaries fluctuated as each one gained temporary ascendancy. Monuments were built, perio-dically destroyed by warfare, and rebuilt, resulting in the inter-mingling of regional styles that characterizes Thai architecture.

By the 12th century, the Thai people had established the kingdoms of Sukhotai in the south and Chiang Mai in the north and had developed a distinctive national culture, including the adoption of Theravada Buddhism spread by missionaries from Sri Lanka.

Theravada is one of three branches or schools of Buddhism which claims to be the oldest and most authentic, transmitted from India to Sri Lanka in the 3rd century BCE. Theravada Buddhism is practiced throughout Southeast Asia; in contrast, Mahayana sects predominate in East Asia and the Tibetan-Himalayan region follows the Vajrayana tradition.

In the 14th century a third powerful Thai kingdom arose in the Chao Phraya River basin. For 400 years the empire of Ayutthaya was the leading political and cultural force in the region, absorbing the neighboring kingdom of Sukhotai, defeating the Khmers of Angkor and extending its conquests as far as Burma. Ayutthaya was eventually destroyed in the Burmese Wars of the late 18th century and the Thai capital was moved south to the site of present-day Bangkok.

The ruins of Ayutthaya lie some 80 km. north of Bangkok along the banks of the Chao Phraya, and a journey by boat offers fascina-ting views of daily life along the river. Approaching Ayutthaya, an impressive panorama suddenly unfolds as the tall spires of the old capital come into view. The monuments display the syncretism of Thai architecture that incorporates influences from the Khmers (corncob shaped prang towers), the Shan (elongated spires) and the Burmese (bell-shaped stupa domes). As a result of this cultural mix, Thailand displays the greatest variety of Buddhist stupa styles of any country in Asia.

Stupas (called chedi in Thai) originated in India, where the rounded shape of ancient funerary mounds was adopted for Buddhist reli-quary monuments. These mounds were often set atop platforms and topped by elaborate umbrellas. Over time each component part of the stupa was given a symbolic meaning and evolved distinctive regional variations as Buddhism spread across Asia.

Wat is the Thai word for temple. Wat Ratchaburana was built in the mid 15th century by the seventh king of Ayutthaya. It features a tall Khmer-style prang tower over the sanctuary, which is covered with stucco decoration, and three porticoes facing east, north and south, set atop a high platform accessed by steep stairs. The silhouette is reminiscent of the medieval Hindu temples of north-central India.

The Thai rulers of Ayutthaya may have also adopted aspects of the royal funerary cult of the Khmers of Angkor and began to erect commemorative stupas to serve as their tombs.

Wat Phra Si Sanphet, built in 1448, is a large temple complex located within the ancient royal palace precinct. Its three graceful bell shaped stupas were built as memorials to encase the ashes of former kings. They typify the Ayutthaya style, where elongated spires of superimposed rings take up almost half the height of the monument. They correspond to the ceremonial umbrellas that top Indian and Sinhalese stupas.

Thailand’s ruling Chakri dynasty traces its lineage to the founding of Bangkok in 1782. Wat Phra Kaew (also called the Temple of the Emerald Buddha) was built inside the royal palace compound by King Rama I to enshrine a precious image of the Buddha which is considered the protector of the country. The temple complex contains many exquisitely ornamented buildings, including three adjacent structures, each one built in a markedly different style: Phra Siratana Chedi, a golden Sinhalese bell-shaped stupa housing Buddhist relics, the Royal Pantheon featuring a Khmer-style prang tower and, between them, the Thai-style Phra Mondop, a library containing sacred Buddhist texts.

The temple complex is enclosed by a wall with a covered gallery painted with scenes of the Ramakien, Thailand’s national epic, de- rived from the Indian Ramayana. Entrances are protected by fero-cious guardian figures in battle attire similar to the masks, head-dresses and elaborate costumes of classical Thai dance drama. Temple guardian images are found throughout Asia, and depict the demonic spirits of ancient nature cults tamed and converted into defenders of Buddhism.

Under the Chakri dynasty the Thai kingdom (known in the West as Siam) prospered, avoiding colonization by the European powers and laying the foundations of a modern nation state. During this period, in the late 18th and early 19th centuries, older architectural models were reinterpreted with the addition of elaborate surface decoration in glittering gold leaf and mosaics of shell, ceramic and colored glass.

The characteristic Thai roof profile also emerged at this time, featuring sloping tiled surfaces with high gables and overhanging eaves enhanced by long pointed finials marking the ends of the ridge poles. The exaggerated effect is reminiscent of southern Chinese architecture which may have inspired it.

Phra Mondop, the sumptuous library building within the Grand Palace’s Wat Phra Kaew temple complex, was built by king Rama I in the late 18th century. It epitomizes the Thai style, with its super-imposed roof structures and overlapping eaves, dramatic upturned finials and richly decorated surfaces.

Wat Pho is one of the oldest and largest wats in Bangkok and contains many historic Buddha images, including a huge gilded reclining Buddha. The 46 m. long statue depicts Buddha’s entry into Nirvana at the end of his earthly incarnations. The soles of his feet show auspicious symbols and chakras, or energy points. Interestingly, Wat Pho is a center for the study of traditional medicine and Thai massage which, like acupuncture, focuses on pressure points affecting the flow of energy in the body.

Chinese influence is more explicit in the use of porcelain mosaics to decorate the surface of chedis at Wat Pho and at Wat Arun, the famous “Temple of the Dawn.” Construction of this magnificent structure was begun by king Rama II over an existing foundation and completed by his successor, Rama III, in the 1840’s. The Khmer-style prang tower is the tallest in the country.

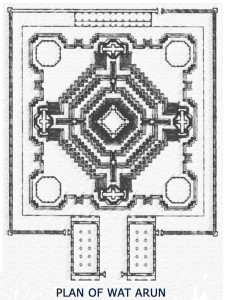

The brick core is covered with plaster and embedded with multi-colored porcelain shards from the ballast carried by Chinese trading ships. The zig-zagging glistening surfaces impart a sense of rhythmic movement to the structure which follows a complex mandala plan. The grouping of five towers represents Mount Meru, the central mountain of Buddhist cosmology, encircled by the guardians of the four directions.

Set in a prominent riverside location, Wat Arun is a distin-ctive beloved Bangkok land-mark. Many of Bangkok’s most famous temples and historical monuments lie on the banks of the Chao Phraya River which winds through the city and the best way to visit them is by a long-tailed motor boat. These water taxis offer a refreshing alternative to the modern city’s notoriously congested traffic.

Set in a prominent riverside location, Wat Arun is a distin-ctive beloved Bangkok land-mark. Many of Bangkok’s most famous temples and historical monuments lie on the banks of the Chao Phraya River which winds through the city and the best way to visit them is by a long-tailed motor boat. These water taxis offer a refreshing alternative to the modern city’s notoriously congested traffic.

Bangkok’s fascinating temples are a welcome respite from frenetic modernity; places of quiet meditation where history comes alive and time seems to stand still.