From the highlands of Oaxaca and Chiapas in southern Mexico the terrain gradually descends towards the Guatemalan region of the Peten, traversed by great rivers like the Usumacinta and covered by dense tropical jungle. Yet this region, which today appears so wild and inhospitable, was for over a thousand years the heartland of Maya culture which reached its apogee during the Classic period from 250 to 900 CE. The tops of the temples at Tikal soar high above the treetops seemingly floating over an endless ocean of green. Tikal is the largest known Maya center. This great city, which in its hey-day covered over 16 square kilometers, built the tallest and most impressive monuments of the Maya world.

The architects of Tikal developed one of the most characteristic elements of the classic Maya temple, the ornamental projections called roof combs which are used to extend the height of buildings. Another important structural innovation was the corbel-vaulted ceiling. The Mayas combined these two elements to build impres-sively tall structures; but the massive walls needed to support the weight of the roofs resulted in very limited interior spaces.

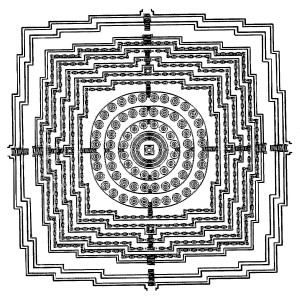

Two great pyramids face each other, as if in dialogue, across the great ceremonial plaza. The tallest is the temple of the Great Jaguar built in the early 8th century CE. Its slender silhouette is made up of nine levels, a number sacred to the Maya, crowned by a tall roof comb that extends the building’s height to an impressive 155 ft. The sculptures covering the roof comb represented a king seated on his throne. He has been identified as Jasaw Chan K’awill, one of the most powerful of Tikal’s rulers whose tomb this was. The pyramids of Tikal most clearly embody the concept of the Maya temple; a sacred space poised between heaven and earth, surrounded by clouds of incense atop a magic mountain where only priests and royalty could step.

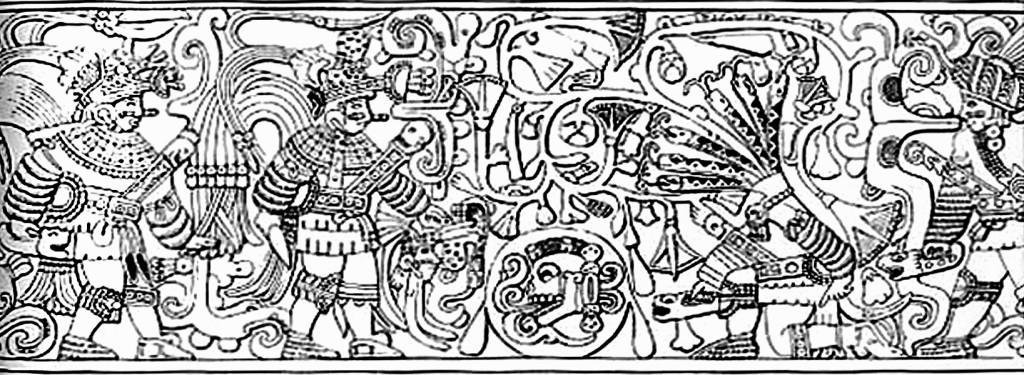

The central plaza is bounded by the buildings of the north acropolis containing the tombs of the ruling families of Tikal. From the begin-ning of the Classic period the Maya erected dated commemorative stone altars and stelae, and a collection of these monuments adorns the plaza. In recent decades, great advances in deciphering Maya hieroglyphic inscriptions and their iconography have revealed that these sculptures represented a cult of the rulers. They memorial-ized their accession to the throne and recorded the alliances, wars and victories of the great dynasties that ruled the Maya city-states.