The temples of Khajuraho are the most sublime expressions of medieval Hindu architecture. Despite its currently remote location, Khajuraho was once the capital of the Chandela Dynasty which ruled most of central India from the 10th to 12th centuries. There were reputedly over 80 temples of which some 20 have survived scattered over a wide area. The most famous are the Western Group located in a spacious park sprinkled with brightly colored bougainvilleas.

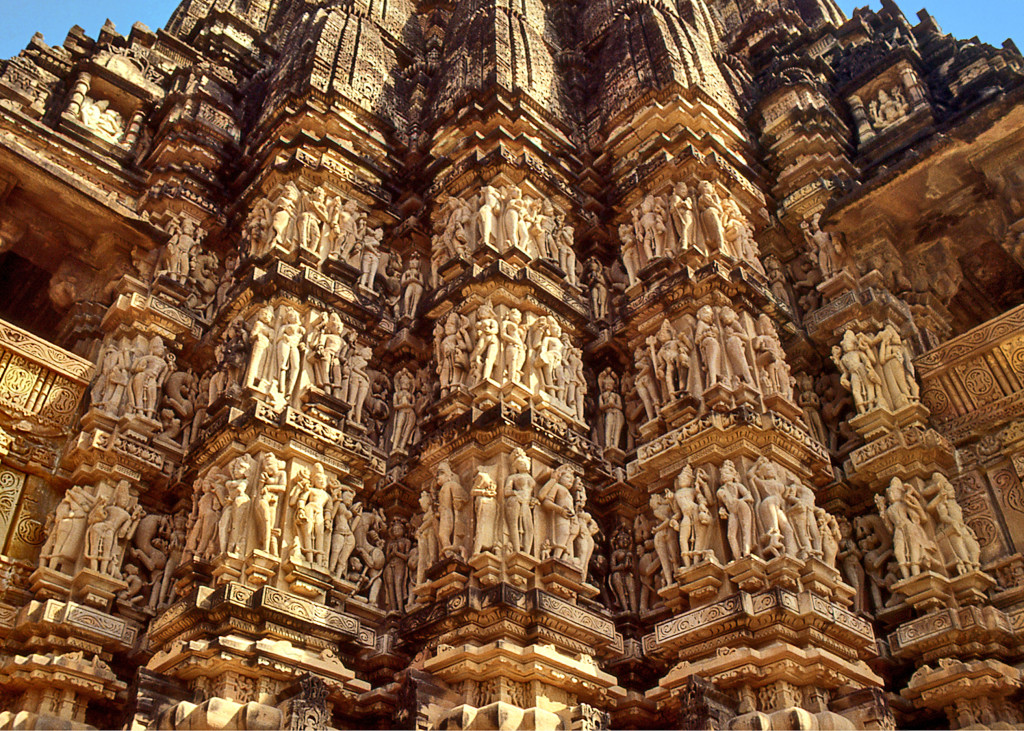

The elaborately carved sandstone temples are elevated on high platforms like sculptures placed atop pedestals. Often four small shrines are added at each corner of the platform representing the cardinal directions, with the main building centered as the cosmic axis mundi. The interior layouts and famous silhouettes of Khajuraho typify the essential elements of a classical Hindu temple. Aligned on an east-west axis to face the rising sun, there is a covered entrance porch leading to a large pillared hall, followed by a vestibule preceding the sanctuary. The worshipers thus proceed through a series of increasingly sacred spaces, leaving the profane outside world in their symbolic journey to the center.

The sanctuary contains the image of the deity to whom the temple is dedicated, and is customarily small, dark and unadorned, resembling a cave. Contrastingly, the structures above with their sculpted profusion of plants, animals, humans and deities, simulate a vast mountain range that rises to a peak. Each section of the temple has a separate roof structure, from the lowest over the entrance porch to the highest over the sanctuary. While the first three have roughly pyramidal shapes formed by superimposed horizontal tiers, the roof section directly above the sanctuary rises as a tall spire called shikhara (mountain peak); its soaring height emphasized by the repetition of vertical bands and other carved decorations.

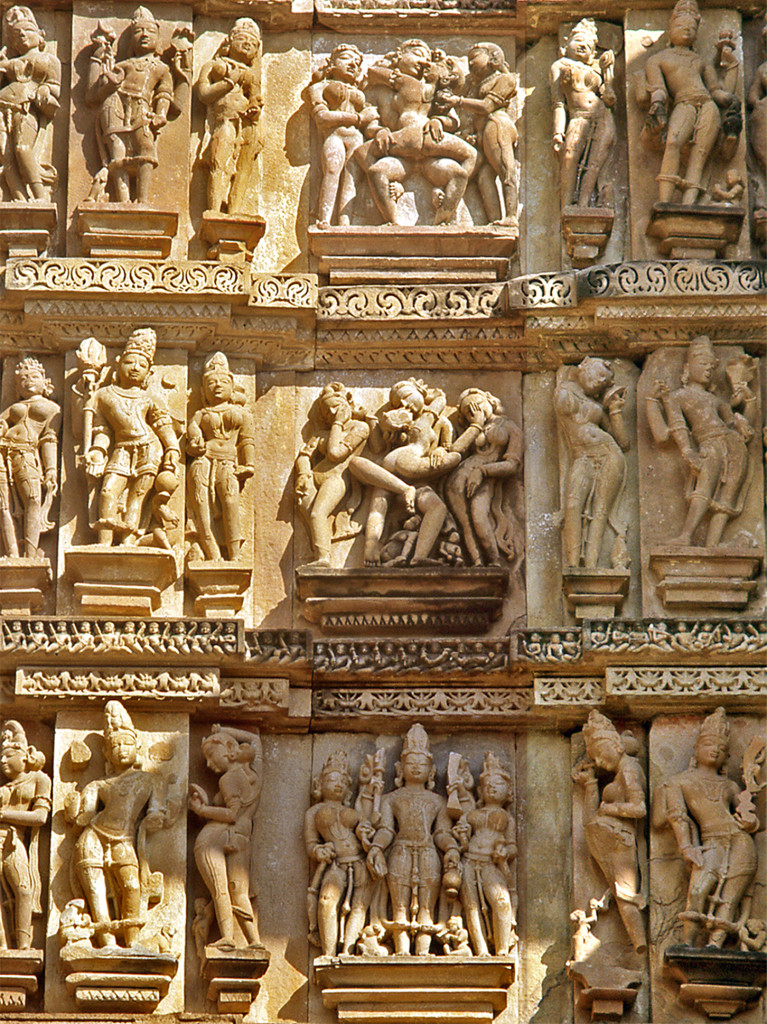

Khajuraho is especially renowned for the exquisite sculptures that cover the outside of the temples with their graceful elongated forms. Not only deities but beautiful men and women are represented engaged in all the activities of worldly life. Many are shown as amorous couples whose acrobatic postures reflect an esoteric code, for Khajuraho was reputedly a center for Tantra, yogic practices exalting the goddess Shakti. Shakti is the creative life energy of the universe manifesting as the feminine principle, Mother Nature, the Great Goddess. Shakti energy can be expressed as sexuality but it can also be sublimated and channeled as spiritual power, for Tantric philosophy teaches to “use the senses to go beyond the senses.”

At Khajuraho, sculpture and architecture meld together in a harmonious synthesis reminiscent of the great European Gothic cathedrals. With their serene expressions, graceful postures and refined gestures that recall the art of classical Indian dance, the sculptures of Khajuraho illustrate our inherent capacity for trans-cendence, from the human to the divine.