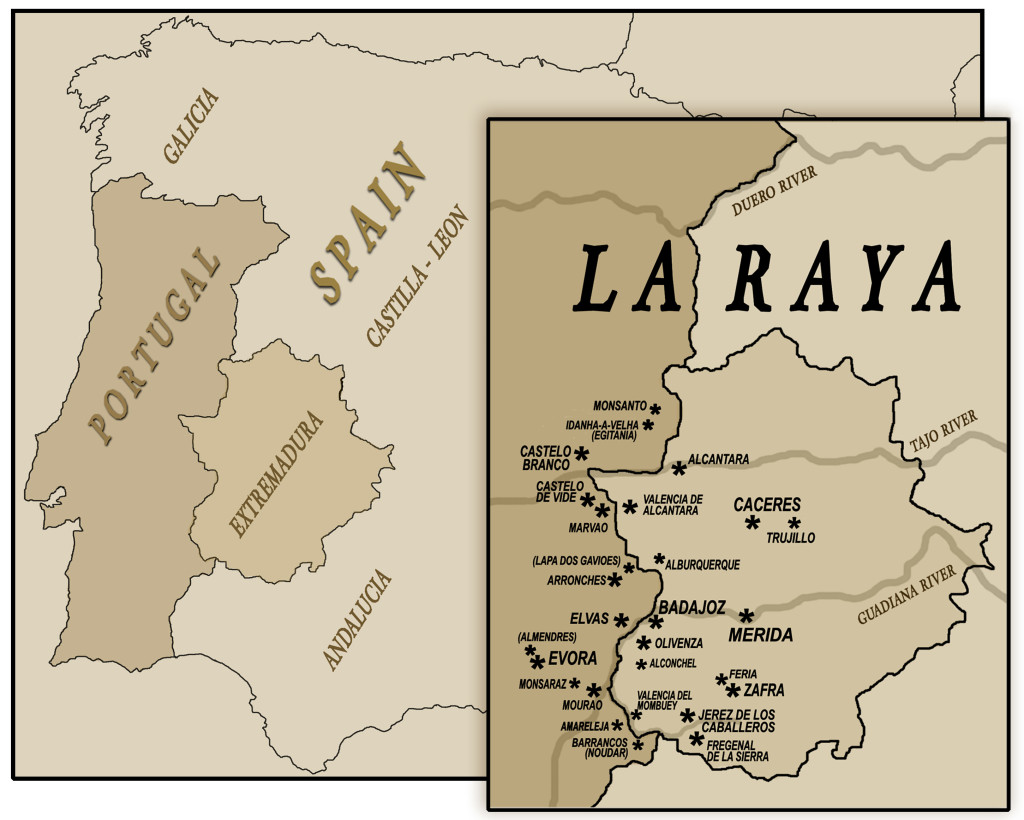

INTRODUCTION La Raya / A Raia (The Line) is the name given to the territories which lie along the borderline separating Spain and Portugal; particularly those in the Spanish province of Extremadura and the neighboring Portuguese Alentejo. Throughout history this region has been a crossroads, a perennial frontier fought over by competing peoples, empires and religions. During the centuries of warfare between the medieval Christian kingdoms of northern Spain and Muslim al-Andalus to the south, contested lands ‘beyond the Duero River’ were collectively known as Extremadura.

It is a sparsely populated landscape of golden grassland dotted with stands of dark green oak and silvery olive trees, where giant boulders rise abruptly like sentinels towering over the endless plains.

The heartland of La Raya is defined by the Tajo and Guadiana rivers and their winding tributaries which have served as territorial markers from time immemorial. But despite shifting political boundaries the region has shared a common cultural heritage since prehistoric times.

PREHISTORY In the dawn of prehistory La Raya witnessed its first clash of cultures as early modern humans spread across Europe displacing the previous Neanderthal population. Archaeological evidence reveals that the southwestern corner of the Iberian Peninsula became the last stand of the Neanderthals, who survived there for millennia after having disappeared (by extinction or assimilation) everywhere else. Fascinating traces of prehistory abound throughout the region. The Maltravieso Cave on the outskirts of Caceres contains rock paintings dating from 23,000 years ago including depictions of animals and numerous outlined hand prints. These hands reach out to us pro-claiming “we were here” in an unbroken chain of human experience stretching across the mists of time.

The Lapa dos Gavioes is a shallow rock shelter nestled in a pine clad hillside near the Portuguese town of Arronches that once sheltered the prehistoric hunter-gatherers of the region. It contains rare open-air rock paintings, dating from the late Paleolithic to the Neolithic periods. The well-preserved pictographs feature red ochre drawings of stylized human and animal figures and geometric patterns of lines and dots whose long-lost message still intrigues us.

At the nature park of Los Barruecos near Caceres huge granite boulders lie strewn across the landscape, piled atop one another like gigantic sculptures, surrounded by ponds and marshes fre-quented by migratory birds and nesting storks. Archaeologists have found here evidence of the first agriculturalists in the region, dating from the sixth millennium BCE. Amidst the rocks there are petroglyphs and ancient tombs carved into freestanding boulders.

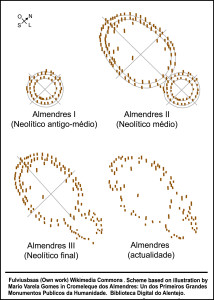

About seven thousand years ago, La Raya was part of an Atlantic megalithic culture that extended from the British Isles to northwest France and the Iberian Peninsula. The great cromlech of Almendres near Evora in Portugal is the oldest astronomically aligned stone circle in Europe, predating Stonehenge. Built from about 6,000 to 4,000 BCE, it is a concentric arrangement of 95 stones marking the changing seasons.

Single standing stones called menhirs are found throughout the region. At Almendres an isolated menhir located northeast of the great circle points to the direction of the sunrise during the winter solstice. La Raya appears to have been a major cultural center for the megalith builders, attested by many impressive sites, including the Menhir of Meada, the tallest standing stone in the Iberian Peninsula located near the Portuguese town of Castelo de Vide.

Menhirs of Almendres (Left) and Meada (Right)

Menhirs of Almendres (Left) and Meada (Right)

Across the Spanish border toward Valencia de Alcantara is one of the largest concentrations of dolmens, or portal tombs, in Europe. These astonishing structures built out of huge stone slabs were originally covered by earthen mounds. Termed ‘antas’ in Portugal, they have long been endowed with magical properties in folk legends that attribute their construction to giants or to magical enchantresses called mouras.

THE LEGACY OF ROME The Roman conquest of the Iberian Peninsula (Hispania) lasted for two hundred years before it was finally consolidated. The Lusitanian Celtic peoples who inhabited the territory of La Raya were among those who resisted with fierce rebellions like the one led by Viriatus in the second century BCE. The region was finally subdued by Julius Caesar in 60 BCE and incorporated into the empire under Augustus, who reorganized the territory of Hispania into the three provinces of Tarraconensis, Baetica and Lusitania. The Guadiana River was the boundary dividing the rich olive growing lands of Baetica (mostly in present-day Andalucia) from the wilder territory of Lusitania which extended from Extremadura to the Atlantic coast of Portugal.

Large country estates were hubs of agricultural production (over twenty Roman villas have been discovered near the Spanish town of Zafra). Olive groves and vine-yards were planted and the famed Iberian pigs fed on the acorns produced by vast stands of oak in the ecologically balanced dehesa system still practiced today.

Large country estates were hubs of agricultural production (over twenty Roman villas have been discovered near the Spanish town of Zafra). Olive groves and vine-yards were planted and the famed Iberian pigs fed on the acorns produced by vast stands of oak in the ecologically balanced dehesa system still practiced today.

Statue of Ceres, Roman Goddess of Agriculture & Fertility, from Merida.

Under Roman rule political stability, combined with improved means of communication and trade, led to rapid urbanization throughout the region. An impressive road system built by the legionaries connected the new urban centers. The famous Via de la Plata ran north from Hispalis (Sevilla) to Emerita (Merida), past Norba Cesarina (Caceres), and on to the rich gold mines of Leon province where the VII Legion was permanently stationed.

Emerita Augusta (Merida) was the capital of Lusitania, first settled in 25 BCE by the veterans of Augustus’ X and VI legions. While the roads, bridges and aqueducts bore witness to Roman engineering genius, Merida’s gleaming marble temples and theaters were designed as showcases to extol and promote Roman civilization.

The Archeological Ensemble of Merida, a UNESCO World Heritage site, has the most extensive and well preserved Roman ruins in Iberia and the outstanding National Museum of Roman Art displays hundreds of sculptures, mosaics, inscriptions and artifacts painting a fascinating picture of daily life in Roman times.

Many towns and cities of La Raya can trace their origins back to the Roman period. While some have retained their importance others have disappeared altogether, by-passed by time, leaving scant remnants of their former glory. Little remains of the once popu-lous Roman city of Ammaia, which flourished between the 1st and 4th centuries CE, along the banks of the Sever River beneath the promontory of Marvao.

Idanha-a-Velha (the Roman Egitania) is a tiny Portuguese village encircled by ancient walls, seemingly set in the middle of nowhere and suspended in time. But this sleepy farming community was once an important early Christian bishopric, the birthplace of Visigothic kings and before that a thriving Roman city which contributed to the construction of the great Alcantara Bridge over the Tajo River.

Dedicated to Emperor Trajan in 103 CE, it is a spectacular feat of engineering that has remained in constant use up to this day. A small temple to the emperor and the gods of Rome also contains the tomb of the intrepid bridge builder, Gaius Julius Lacer. It sits on a bluff above the river overlooking his enduring creation.

AL-ANDALUS The 4th and 5th centuries CE saw the gradual dissolution of Roman power in the wake of successive waves of invasion by Germanic tribes in their westward migration across Europe. From among these, the Visigoths won a tenuous hold over the Iberian Peninsula, ruling a fractious kingdom from their capital at Toledo. When the king’s rivals sought help from allies in North Africa, an army of Berbers newly converted to militant Islam found the territory of the Visigoths ripe for conquest. In 711 the Umayyad general Tariq led an expe-ditionary force across the Straits of Gibraltar (Jabal Tariq or Tariq’s Mountain) and toppled the weakened kingdom.

Merida, which had retained its wealth and importance under the rule of powerful Christian bishops, fell after a protracted siege in 713. La Raya became part of al-Andalus, (the name given to the Iberian territories under Muslim rule) subject to the powerful Caliphate of Cordoba and, after its fragmentation, to the independent Taifa Kingdom of Badajoz.

For the most part, different cultures and religions coexisted peace-fully in al-Andalus; but ethnic divisions within Muslim society and the heavy tax burdens imposed on the Christian population led to sporadic uprisings. The 9th century rebel leader Ibn Marwan, whose Galician ancestors had converted to Islam and become governors of Merida, typifies the mixed society and fluid alliances of the times. He led a rebellion against the Caliphate, fleeing to the impregnable fastness of Marvao and allying with the Christian Kingdom of Leon. He was eventually granted his own lands by the caliph, where he founded the city of Badajoz (Batalyaws) and began construction of its magnificent Alcazaba fortress.

The historic city of Evora, an ancient megalithic center and thriving Roman town, was ruled by the Moors from the 8th to the 12th centuries. During the Reconquista it was taken by the legendary Portuguese warrior Geraldo Sem Pavor (Gerald the Fearless). Famous for his daring surprise attacks, he led a successful guerrilla war against the Moors throughout the Alentejo and Extremadura from 1162-1172, capturing numerous castles and towns. Taken prisoner during the siege of Badajoz, Gerald was forced to relinquish most of his conquests in exchange for his freedom. The wily adventurer finally met his end in Morocco where, accused of espionage, he was executed by the Almohads.

View of Evora Cathedral and Cloister, Portugal

View of Evora Cathedral and Cloister, Portugal

Begun soon after Geraldo’s conquest, the Cathedral of Evora was built in a robust Romanesque style. The stone walls topped with crenellations impart an imposing military air to the structure. Battlemented square towers flank the plain façade which was em-bellished with a finely sculpted portal and rose window in the 14th century, when the beautiful Gothic cloister was also added.

Badajoz remained an independent Muslim kingdom ruling over the territory of La Raya until 1230, when in the course of the Recon-quista it fell to the king of Leon. Construction of the cathedral of Badajoz began shortly thereafter and would continue on and off until the 16th century. Its massive plain exterior lacks the airy grace of flying buttresses and large stained glass windows typical of the prevailing Gothic style. Instead, due to scarce resources and the practicalities of defense it stands, literally, as a fortress of the faith.

RECONQUISTA By the 9th century, only a strip of land at the northernmost edge of Spain remained in Christian hands. This small enclave would later grow into the kingdoms of Leon, Castile and Aragon and launch the Reconquista, the centuries-long struggle to wrest the peninsula from Muslim rule. For all that time La Raya was a perpetual battlefield, subject to the ebb and flow of changing boundaries; as a result large areas became depopulated. To this day, Extremadura remains the least populous region of Spain.

To assist with their ongoing crusade the Christian kings relied on military orders like the Templars and Hospitallers who, together with the Spanish Knights of Santiago and Alcantara and the Portuguese Knights of Christ and Avis, were granted fiefdom of re-conquered lands. To that end, the military orders and feudal nobility alike vied in building the numerous fortified castles which still dot the country-side. Throughout La Raya their remains can be found perched atop almost every natural elevation, seemingly growing out of the rocks. Their lofty towers and crenellated walls command sweeping views of the landscape guarding against the approach of enemy armies.

The spectacular promontory of Monsanto (the ‘mons sanctus’ cited by Roman historians) was sacred to Celtic peoples of the region. The impregnable heights resisted the Romans and Moors alike. Its powerful mystical am-biance was recognized by the Portuguese Templars who built a fortress here in the 12th century, incorporating the massive granite boulders into the structure, as do many of the old stone houses in the picturesque town that clings to the steep slopes below.

Most of southern Extremadura was controlled by the Knights Templar from their headquarters at Jerez de los Caballeros and imposing castles at Alconchel, Fregenal de la Sierra and Burguillos del Cerro. In 1312 facing charges of heresy and the dissolution of their order, Templar knights staged staged a bloody last stand at their fortress in Jerez de los Caballeros choosing death over surrender. Their landholdings were forfeit to the Crown which sold or granted them to loyal families among the nobility.

Massive Keep of the Castle High Above the Town of Feria, Spain

Massive Keep of the Castle High Above the Town of Feria, Spain

The Dukes of Feria, based in Zafra, thus became powerful feudal lords owning vast territories throughout the region. Landholding patterns established in response to the challenges of the Reconquista gave rise to the latifundia common in Extremadura; where huge tracts of land, neglected by absentee owners and worked by impoverished peasants, long hindered economic development.

WORLDS WON & LOST 1492 was a momentous year for Spain. It marked not only the discovery of the New World, but the conclusion of the Reconquista with the fall of Granada, the last bastion of Islam in the peninsula. It also marked the expulsion (or forced conversion) of Muslims and Jews and the beginning of a downward spiral of religious and social intolerance exemplified by the Inquisition.

After five centuries as part of al-Andalus, there were large Muslim populations and Jewish communities throughout the region. The loss of so many farmers, skilled artisans and traders would disrupt and impoverish the economy of La Raya.

The beautiful Portuguese hilltop town of Castelo de Vide boasts a well preserved medieval Jewish quarter. Walking along the steep cobblestone streets visitors can still find ancient stone doorways indented to hold a mezuzah. The former synagogue, restored as a museum, displays the names of victims of the Inquisition (established in Portugal in 1536 ) as a reminder of what was lost.

View of the Town and Ancient Doorway, Castelo de Vide

View of the Town and Ancient Doorway, Castelo de Vide

But the exploration and conquest of the Americas opened up new horizons for ambitious adventurers and warriors hardened by centuries of the Reconquista. Most of the explorers and conquis-tadors of the Americas hailed from Extremadura, including Cortez and Pizarro, the conquerors of the Aztec and Inca empires.

Statue of Pizarro and City Walls of Trujillo, Spain

Statue of Pizarro and City Walls of Trujillo, Spain

When Indianos (those who had made their fortune in the Americas) returned to their hometowns they built mansions to proclaim their new-found wealth and status. The spectacular walled historical quarter of Caceres (a UNESCO World Heritage Site) reflects this construction boom with its magnificent panoply of Spanish Renaissance buildings. Rivalries played out architecturally as prominent families competed to build the grandest houses and the tallest towers.

The Portuguese were great navigators who led the Age of Discovery from the 15th to the 17th centuries, acquiring a vast overseas empire and controlling the lucrative trade between Asia and Europe. Portuguese territories extended eastward from the African coasts to India, Southeast Asia and China, and west across the Atlantic to Brazil. Belem Tower, built in 1514 to guard the mouth of the Tagus River as part of the coastal fortifications of Lisbon, is emblematic of Portugal’s maritime achievements.

The discovery of gold and diamonds in the Brazilian state of Minas Gerais, made Portugal the wealthiest country in Europe in the 18th century. This era of prosperity was reflected architecturally in beautiful buildings of a distinctively Portuguese Baroque style that incorporates azulejos, blue and white decorative tiles, inspired by imported Chinese porcelains and Dutch imitations from Delft.

The gardens of the Episcopal Palace in Castelo Branco, created in 1725, are among the most beautiful Baroque gardens in Portugal. Its clipped hedges, fountains and statuary featuring Portuguese monarchs, Christian saints and allegories of the zodiac, the seasons and the continents represent a cultural compendium of the age.

THE DISASTERS OF WAR In the 16th century, under Charles V and Phillip II, Spain had reached the height of its power, reflected in the literary and artistic achieve-ments of the Golden Age. But Spain’s rulers squandered the vast wealth of the Americas in a series of ruinous religious and territorial wars. Not least of these, the Portuguese Restoration War (1640-1668) that devastated La Raya.

The kingdom of Portugal had become independent from Spain in the 12th century, but had briefly reverted to Spanish rule under the Hapsburgs. Marriage alliances between Portuguese and Spanish nobility resulted in shifting boundaries and competing territorial claims (sovereignty over the town of Olivenza is still disputed). The Spanish town of Valencia del Mombuey, sacked and twice burnt to the ground by Portuguese troops, is emblematic of the period.

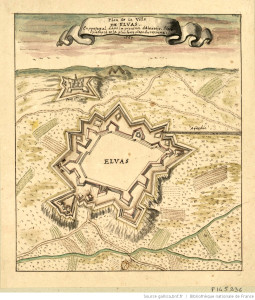

At this time, warfare was being dramatically transformed by the widespread adoption of gunpowder and cannons. Ancient walls that had withstood assault for centuries were now suddenly vulnerable to artillery fire. In response, a new style of fortification arose; star-shaped forts were designed in complex shapes with projecting triangular bastions and massive sloping earthworks.

Star forts originated in Italy in the mid 16th century and quickly spread to the rest of Europe, reaching their apogee with the designs of Dutch and French military architects in the 17th century. The extensive fortifications of the Portuguese town of Elvas (a UNESCO World Heritage Site) are among the best-preserved in Europe, and are mirrored across the frontier by the bastions of Badajoz.

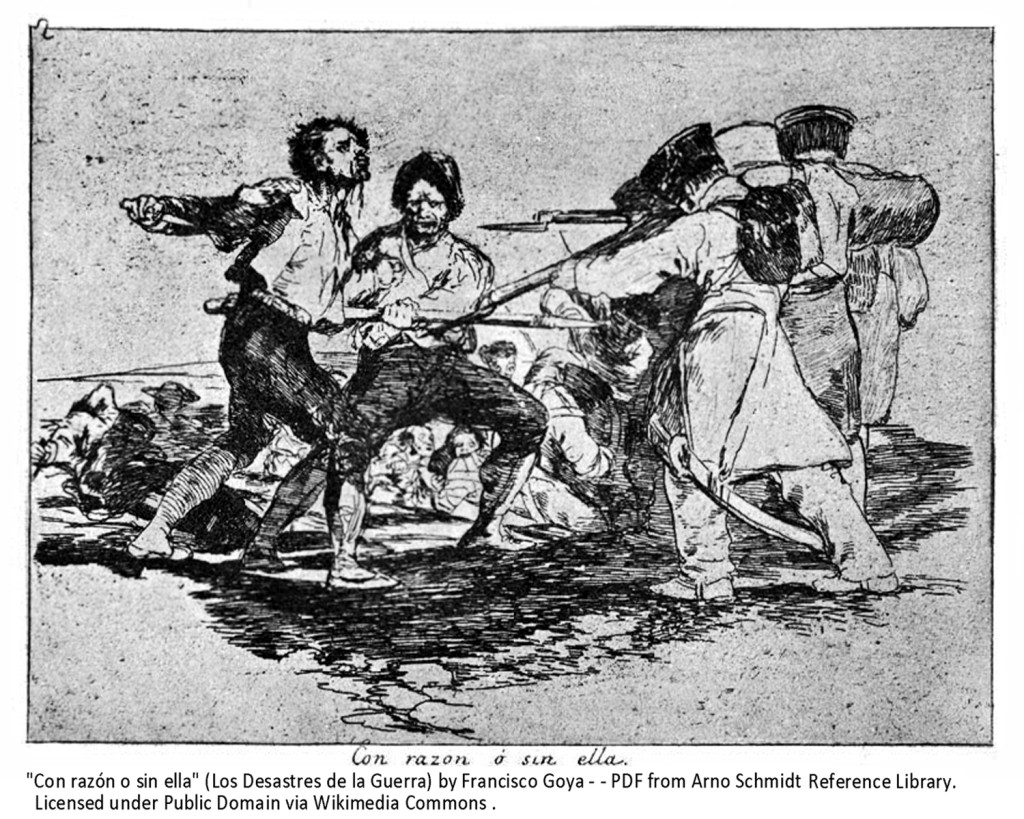

In the early 19th century, Napoleon’s territorial ambitions would have dire consequences for Spain and Portugal. The forts of La Raya were the scene of major battles between the British-led Alliance and French forces in the Spanish War of Independence against Napoleon (1807-1814) as the region was again subjected to the violent depredations so vividly portrayed in the contemporary paintings and prints of Goya.

INTO THE MODERN AGE At the turn of the 20th century, Extremadura enjoyed a period of prosperity and commercial expansion fueled by new technologies and improved means of communication. Newly built railroad lines spurred the growth of regional urban centers like Merida and Badajoz, where wealthy merchants built grand storefronts and mansions in fashionable styles like Andalusian Regionalism and the Modernista architecture of Gaudí.

The Spanish and Portuguese empires had crumbled in the course of the 19th century as their former colonies gained independence; an economic reversal that would have far reaching social and political consequences. The progressive ideas of the ’98 Generation and the Spanish Second Republic now spread to towns like Fregenal de la Sierra, where a liberal newspaper was published, agrarian reform was promoted and civic improvements carried out. But persistent socioeconomic problems led to protests and upheavals and ultimately to the bloody Civil War (1936-1939) bitterly fought in Extremadura. For centuries families in La Raya had intermarried across the border. During the Civil War many Spaniards fleeing persecution found refuge with relatives and friends in Portugal.

In the following decades, the region experienced massive emigration in search of economic opportunities. While cities like Badajoz grew rapidly, their historic centers ringed by blocks of modern buildings, many small towns saw their populations age and decline. But tech-nology can now connect the smallest town to worldwide networks.

The region could also benefit from the development of renewable energy resources like its abundant intense sunshine. In 2007 the tiny Portuguese town of Amaraleja became home to the largest solar power plant in Europe and a smaller plant operates across the border in nearby Valencia del Mombuey.

There is renewed interest in the sustainable ecological practices of the ancient dehesa system, and traditional agricultural industries (like the famed Iberian ham) continue to be economic mainstays. The Portuguese Alentejo region is the world’s largest producer of natural cork, and is enjoying a burgeoning wine industry.

The Alqueva reservoir of the Guadiana River created the largest artificial lake in Europe and is being developed for agricultural and recreational uses. A growing number of tourists are, at long last, discovering the region’s fascinating historical monuments and un-spoiled picturesque countryside. For the soul of La Raya resides in its small towns; the ancestral roots families return to, where cherished traditions are preserved.