In the first centuries of the Common Era, Indian traders began expanding their sphere of influence throughout Southeast Asia, establishing outposts that eventually flourished into independent indianized kingdoms. Their trade routes also spread Indian culture and religious ideas in a syncretic mix of Hinduism and Buddhism (which still coexisted at that time) colored by mystical Tantric elements. This Indo-Javanese period spans from the 7th to the 10th centuries CE, when the Sailendra dynasty ruled Java, Sumatra and the Malay Peninsula.

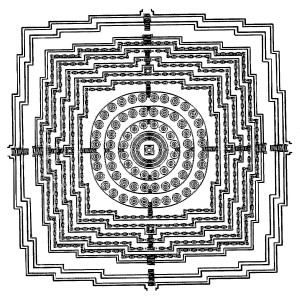

The Sailendras were Buddhists, and their greatest achievement was the construction around the year 800 CE of Borobodur, the largest Buddhist monument in the world. This unique structure, built atop a low natural hill in central Java, is a three-dimensional architectural mandala. It is not a building in the normal sense of the word, as it is completely open to the sky and has no interior spaces. Its design incorporates the symbolism of Mount Meru (the sacred mountain at the center of Hindu and Buddhist cosmology), the geometric patterns of a mandala diagram (used to focus psycho-spiritual energies), and bell-shaped stupas (Buddhist monuments housing holy relics).

The scale of Borobodur is impressive: the monument rises up nine levels as a series of receding terraces that form a truncated pyramid. The base platform, shaped as a square with indented corners, measures 370 ft. on each side. It is surmounted by five square terraces and three circular ones, linked by four stairways that rise to the summit, which is topped by a large bell-shaped stupa.

Pilgrims traditionally ascend the eastern stairway to begin their clockwise circumambulation of the monument; a complete circuit of the four square terraces covers a distance of 3/4 of a mile. The square terraces are surrounded by balustrades that create partially enclosed galleries which are open to the sky. The galleries are decorated with over 500 life-sized Buddha images and some 8,202 linear ft. of exquisitely carved relief panels.

The entire sculptural program is conceived in didactic progression. Reliefs on the base level offer lively depictions of contemporary life that illustrate the workings of karma, the spiritual law of cause and effect, in human affairs. Most of these carvings were later covered up by the wide platform built in order to stabilize the structure. The relief carvings on the first terrace feature scenes from the life of the historical Buddha and fantastic tales of his earlier incarnations called Jatakas. These panels contain some of the most famous images from Borobodur. The next four terraces depict the education of Sudhana a young man who serves as a model for the spiritual seeker of Buddhism. The imagery of the upper galleries becomes progressively more esoteric as it focuses on the bodhisattvas, transcendent saintly figures of the Mahayana pantheon and their philosophical teachings.

In the upper circular terraces we pass from the world of forms into formlessness; from the wealth of figurative detail which decorates the lower terraces into pure abstraction. Seventy-two hollow stupas are arranged in three concentric circles, each one pierced by small diamond or square shaped openings that allow only partial glimpses of the Buddha images inside, all seated in the pose of preaching the first sermon, called “Setting in Motion the Wheel of the Law.”

The enclosed galleries of the lower terraces obscure the view so a person cannot see very far beyond their immediate surroundings; forcing one, as it were, to focus on the teachings being presented at whichever stage of the journey one is at. But once the topmost circular terraces are reached, suddenly the space opens up offering a magnificent 360-degree view of the light-filled surrounding plain. This exhilarating experience vividly illustrates a spiritual seeker’s progression from the darkness and limitations of ignorance to the clarity and boundless freedom of enlightenment.

Borobodur is a three-dimensional interactive exposition of Buddhist doctrine, capable of transforming consciousness through its very design. The pilgrim gradually ascends the sacred mountain while circumambulating in spiral fashion each level of the mandala, undergoing in the process a symbolic transformation; leading from the depths of ignorance, upward through successive stages of increasing self-awareness and knowledge of the dharma, to the final achievement of the heights of spiritual transcendence in nirvana.